Whakaahua, 2019

In Te Reo Māori (the Māori language) whakaahua, in simple translation, means photograph. I went to art school in 2006 believing I was a painter and walked out as a photographer. In fine art photography, wearing little white gloves to handle photographs never felt comfortable as a brown girl. In 2011, I began learning how to weave, embracing the tactile and using my hands to repeat the patterns of my ancestors. For my Master of Fine Art, I began combing photography and Māori customary weaving. Here, I produced a series of photographic works that I wove using found photographs of weavers in raranga, kete whakairo (finely woven patterned Māori baskets) patterns. This project expanded when I began weaving portraits of my weaving circle Sistars in kete patterns from their ancestral homelands.

When I began my PhD in 2015, I noticed an apparent divide between Fine art and customary practitioners of Māori art. For example, Diggeress Rangituatahi Te Kanawasays,“…there is no excuse for not using traditional materials”[1], while Deidre Brown argues, “…there is a long history of new tools enhancing Māori cultural expression…digital media is no exception”[2]. Indigenous arts practice has always been marked by continually shifting ground. Like other indigenous art forms, Māori art cannot be reduced and confined under a singular, unified heading. Following the lead of Robert Jahnke, I use the term customary Māori art to mean art, that “maintains or mimics traditional visual referents[3]”. Māori customary art is inevitably and inherently linked to the past and has a specific colonized history. While its demise has been lamented since the practices of Te Whare Pora (the House of Weaving or Weaving School) were first recorded[4], Māori weaving continues to thrive in Aotearoa and beyond.

I started my research project with the following questions; are expatriate Māori weavers bound to the same cultural materiality constraints concerning preservation of culture when living on another land? Can new technologies, such as digital imaging be combined with customary art techniques without damage or loss to indigenous customary practices? Can digital photographic processes and production be allied with indigenous methods of making – not just as a conceptual representation or thematically, but to make the process of digital art making, in itself, indigenous.

The journey that I have taken to get to this exhibition has been more than four and a half years in the making. I have used previous exhibitions as testing grounds for earlier versions of works in this show; such as Digital Mana, 2018, Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP)and Te Ao Moemoea/The land of Dreaming, Carlton Library Light Boxes, 2019 City of Yarra Exhibition Program, 667 Rathdowne Street, North Carlton, 21 March – 20 September, Bowness Photography Prize (2018), Monash Gallery of Art (MGA), Wheelers Hill.).

The 10 framed photographs that line the walls of Gallery One in Blak Dot portray macro (extreme close up) shots of whatu/ Māori cloak weaving samplers that I have woven and then photographed. In reference to my own vantage point of a Māori-Australian, the feathers I have used are from Australian native birds, rather than New Zealand birds. For Māori, the highest prestige garment that can be woven is the Kākahu Huruhuru or feather cloak. For this exhibition I have reworked a cloak shown at CCP and MGA. This resolved iteration includes tāniko (finger weave, embroidered border for cloaks) in a pattern called Aramoana (also known as ocean pathway), chosen for its resonance for me as Māori diaspora.

Looking out towards the gallery entrance is a large photographic wallpaper printed with a half-tone effect. I took this image in June this year while visiting my marae. Having left my shoes at the door, I stood in front of my wharenui/ancestral house, sheltered under the maihi or carved gables of my whare/house, these carvings represent the two carved outstretched arms of the ancestor. This wall paper piece both shelters the work inside the gallery, while challenging the role the photograph has had as a tool of colonialism, presenting the view from an indigenous gaze looking out.

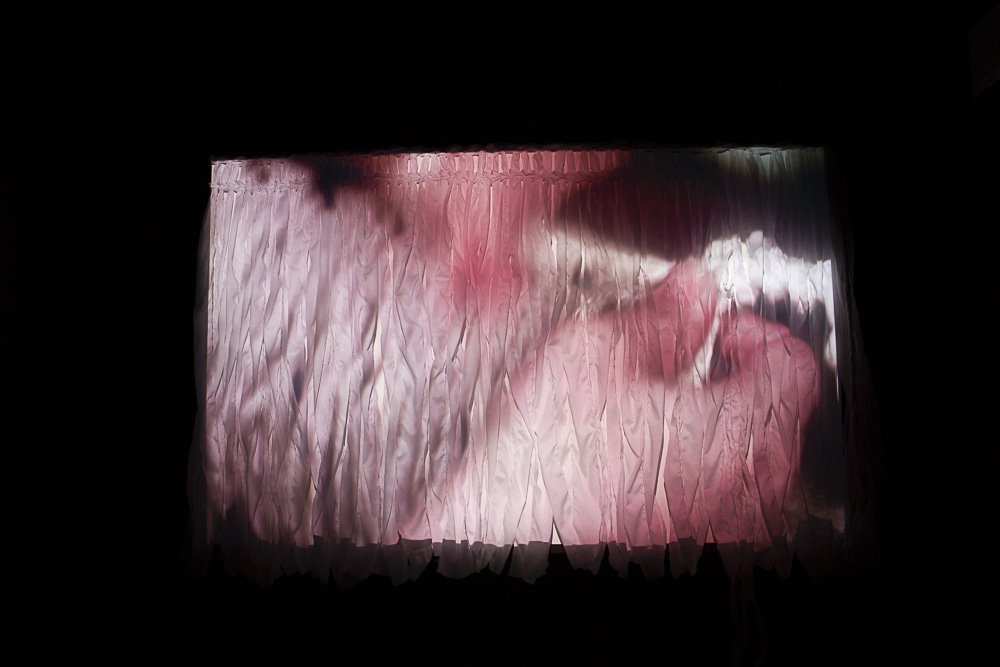

Gallery two shows a video work of the process of weaving Gundulu/Emu Kākahu huruhuru, 2018-2019. In particular, the tāniko border, the whatu stitch, māwhitiwhiti (a cross over stitch also known as whale tail) and the finishing stitch or braid. This is projected against a woven screen cast-on using a tāniko technique using and as tarting row of whatu.

I initially struggled trying to find a title for this exhibition; I wanted a one or two word title that expressed this research project; so that Māori weaving is not simply cast as the subject of the colonizer’s camera machinery but is instead rethought and repurposed as an indigenous weaver’s medium. In this, photography is no longer thought of and deployed as the medium of record, but rethought, repurposed and reworked as an indigenous maker’s medium. For inspiration, I returned to Te Reo and looked up the word, “transform” on the Maori dictionary online. To my surprise (but I should not have really been surprised, as I have learnt the Māori world is full of such lessons), the word I wanted was my own medium;

Whakaahua

1. (verb) (-tia) to acquire form, transform.

2. (verb) (-tia) to form, fashion

3. (verb) (-tia) to photograph, portray, film.

4. (noun) photograph, illustration, portrait, picture, image, shot (photograph), photocopy.

5. (noun) design[5].

[1] (Te Awekotuku 1991, p119)

[2] (Brown 2008, p 60)

[3] (Jahnke 2011, p. 135)

[4] (Best 1898, p. 658)

[5] (Te Aka Māori-English, English-Māori Dictionary Online 2019, para 1)

Blue Princess Parrot (2018)

New Brown Goshawk (Raptor) (2019)

New Koel (Raptor) (2019)

New Dollar Bird (Native Kingfisher) (2019)

New Laughing Kookaburra (Native Kingfisher (2019)

Conclurry Rosella (Parrot) (2018)

New Kestral (2019)

Galah (Cockatoo) (2018)

New Emu (2019)

Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo (2018)

Gundulu/Emu Kākahu huruhuru, 2018-2019, Installation image at Blak Dot Gallery 2019

Whatu Process (2019), Still image of video work, shown in Gallery Two, Blak Dot Gallery as part of Whakaahua

Sheltered under the arms of the ancestor: Weraroa Marae June 2019